Future of Mental Health

Innovation Design Engineering | Solo Project 2020

The goal of this project was to explore the pain points of the recovery journey for depression and identify ways to support the young adults in moments of need. The project does not aim to replace professional therapy, but acts as a bridge between the user and therapy, connecting the two (like a bridge over troubled water). The project has changed over the course of time, and is now focusing on prevention and assisting young adults in building healthy mental habits.

Studies have shown that mental disorders are on the rise in recent years. Chances are, we either know someone who is affected, or are affected ourselves. According to the 2013 Chief Medical officer report, untreated poor mental health cost £70- 100 billion in GDP in the UK in 2013. Depression specifically is one of the leading causes of living with a disability worldwide.

Life has ups and downs, and it’s normal to feel sad. However, depression isn’t just sadness. It’s a sense of hopelessness that seeps into every corner of your life, sapping joy out of daily activities. Depression doesn’t just affect mood, it also has a cascading effect on many aspects of our lives, including but not limited to: productivity, physical well-being, memory, decision making, and sleep quality. Depression also makes one more susceptible to chronic diseases like diabetes or cancer.

Though depression can affect any age, 19.7% of people in the UK aged 16 and over showed symptoms of anxiety or depression. Suicide is also the second highest leading cause of death in 15-29 year olds.

Background Research

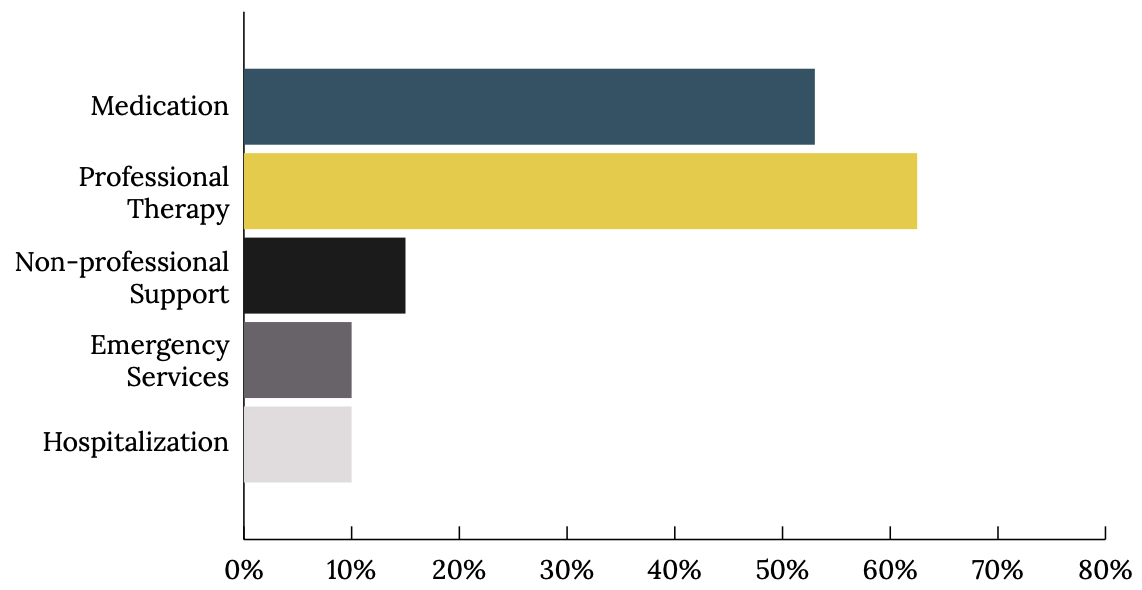

Psychotherapy methods such as CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) is one of the most effective forms of therapy, even better than medication. Cognitive therapy was found to have only a 31% relapse rate, while antidepressants had a relapse rate of 70% in a 12 month period. It works so well because it targets the negative thinking pattern that often causes people to spiral into a depressive episode.

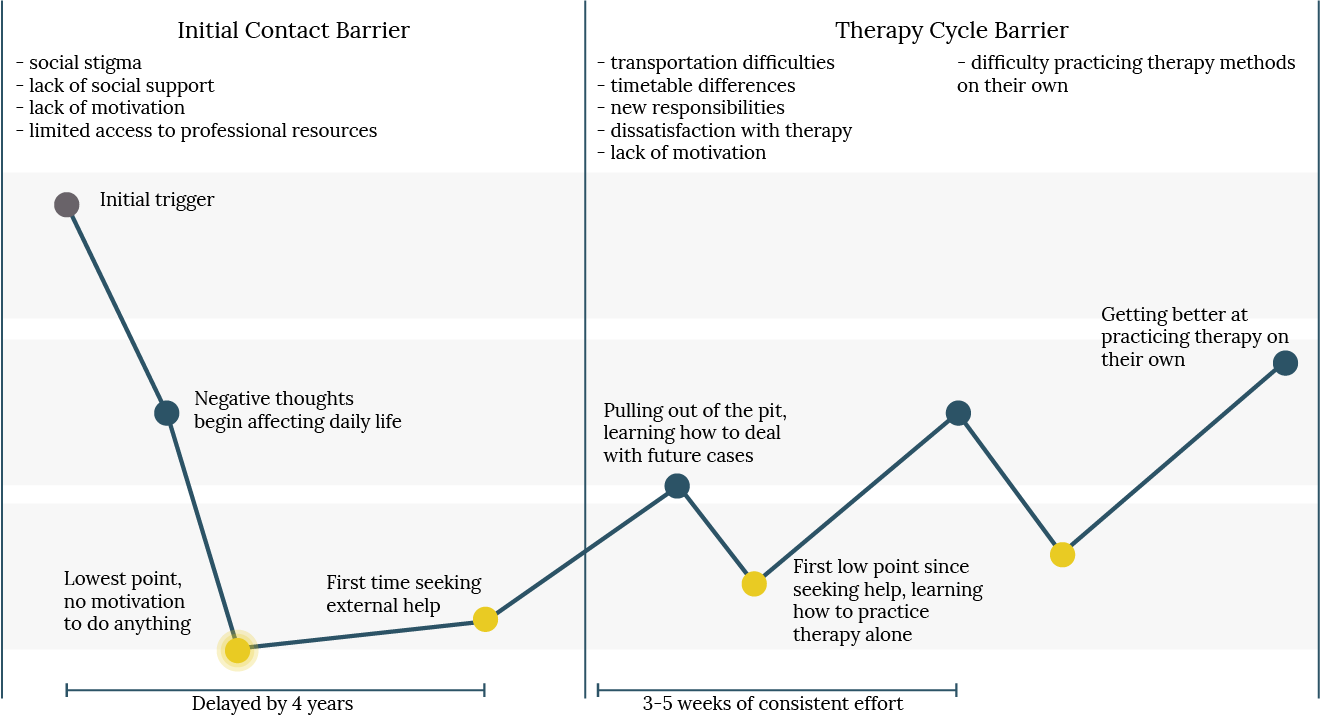

In spite of this, a survey conducted in 2013 found that 31% of people don’t seek professional help. Of the 69% that do seek help, only 62.5% seek professional help. Even then, treatment is usually delayed by 4 years.

I conducted empathy interviews with 4 individuals who had battled or are currently battling depression to learn about their journey. These insights combined with insights from research papers led me to the following main barriers to therapy.

• Social stigma can start as overall cultural attitude attributing negative connotations to mental illnesses and discrediting the validity of mental illness, which can become internalized by the individual, resulting in self-stigma, an increase in negative self- talk (seeing depression as a personal weakness), denial, and lack of motivation to seek help.

• Lack of social support is also typically the result of social stigma in which people surrounding an individual battling depression does not recognize it as a valid problem and doesn’t encourage the individual to seek professional help.

• Lack of motivation typically happens as depression sets in. A common symptom of depression is lethargy, as daily activities feel pointless. This can make it even more difficult in wanting to seek help and change the situation.

• Limited access to professional resources caused by either lack of time or money in order to properly seek therapy. This is especially true for people ages 15-29 who are juggling multiple responsibilities and may not be financially independent yet.

It’s not just the initial contact that has barriers, but maintaining therapy sessions and practicing therapy methods like CBT on your own can be difficult as well. From interviews, people learning how to catch themselves when they’re having a negative thought spiral and change their mentality takes practice.

One individual said it took her up to 3 weeks before she began to get the hang of it. A study showed that drop-out rates for therapy were up to 47%. Another study found that most drop-outs happened around the 14th session. Of the 43% that dropped out in this study, 46.7% said that they were not motivated or were unhappy with the therapist or treatment. 40% reported external reasons, such as transportation difficulties, lack of time or new responsibilities. Only 13.3% said that they dropped out because they saw an improvement and did not feel like they needed further treatment. Analysis of successful treatments showed that 50% of participants need around 21 sessions in order to reach clinically significant improvement.

The journey in battling depression is not a smooth upward slope, but filled with ups and downs. Therefore, it’s important that support is readily available and easily accessible for the individual whenever they need it. This is difficult for therapists to accomplish on their own, but could be achieved by working with smart systems to extend their presence.

I spoke with Dr. Amy Hardy, a research clinical psychologist, and Helen Moss, a psychotherapist and counselor, and they both reaffirmed that a lot of times, getting people to start therapy and to continue it is difficult. Being able to use an AI system to extend their reach so that clients have a guidance system available to them 24/7 would be helpful. Also being able to have access to a record of what happens outside of therapy would be beneficial to both the client and therapist.

Depression is also progressive. Data shows that after the first episode, the likelihood to experience a second episode within 5 years is 50%. After the second episode, likelihood increases to 70%, and by the third, 90%. The duration of each episode will become longer and the gap between each episode, shorter. Therefore it is ideal if depression is identified and treated as early as possible in order to prevent relapse and minimise emotional and financial burden.

How do people feel about using AI for mental healthcare?

A survey conducted by PWC found that 60% of people ages 18-34 are willing to talk to an advanced computer or robot with AI to answer health questions, diagnose their condition and recommend treatment. In another study to research willingness to be vulnerable with a robot system, they used Ellie as the example. Ellie is a robot therapist used to screen soldiers for PTSD. In the study, half of the people were told Ellie was being controlled by a human and half were told Ellie was just a robot. It found that people were more willing to betray signs of sadness and were twice as likely to disclose personal information when they believed Ellie was just a robot.

Initial concept diagram

Identifying project space

Experiments

This project uses a DMI approach in order to find the best fit for the solution embodiment. As covid-19 began to affect daily life, it was difficult to do as much physical prototyping and in-person experimentation as I wanted to, which was a shame. Nevertheless, I tried my best to emulate situations and carried out surveys and interviews with users instead.

The ultimate goal of this project is to identify the embodiment and interactions for a mental health monitoring and guidance system for young adults.

Each round of experiments addresses an aspect of this and comes together in the end to inform the design decisions of the end solution. There are still many unanswered questions, but hopefully this project helps to shed light on certain topics that were only touched upon briefly in previous papers.

Acceptance

Physical vs Mental health

Although currently people less inclined to see a counselor as readily as they would see a doctor, they are still just as willing to be monitored for their physical and mental health.

Methods of monitoring

The questions were followed up by which method of monitoring people were most comfortable with, including levels of preferred control. Here are the responses for methods of monitoring, from most to least accepting:

Text based interaction

Video/images

Voice/ambient sound

Blood pressure

GPS

Blood tests

Social Media

People were only slightly more reserved about being monitored for mental health than physical health. The findings also were in line with the AI ethical guidelines laid out previously, in that people were comfortable when they had more autonomy and control of the system.

There was the least resistance to text based interactions, and people were most open to being prompted for interactions. Surprisingly, there were more people open to being monitored by voice or video constantly in the background than I originally anticipated. Another surprising find was that people were slightly more open to video monitoring than voice/ambient sound monitoring.

Rituals

A survey was also conducted to examine what current objects/ activities/routines bring people comfort. After categorizing the responses, here is the ranking:

Distractions (passive consumption) (20)

Meaningful relationships (18)

“Emotionally durable design”

Engaging activities/hobbies (8)

Exercise (4)

Rituals (3)

An interesting insight was that meaningful relationships were not just limited to family, friends or pets, but also included inanimate objects such as stuffed animal, bike, etc. An interesting note to keep in mind is “emotionally durable design”. One individual said that for him, he formed a deeper attachment to his bike because not only did his bike serve him, he also had to work and put time and effort into maintaining his bike. This can be tied into a separate insight from earlier in the project where it was mentioned how beneficial pets were in helping them get through depression. Having a pet can provide companionship, routine, some exercise and a sense of purpose. Therefore, a sense of responsibility and purpose is an important element to keep an individual motivated to stay engaged.

Motivations

I compared two existing apps to test users motivation and engagement. I picked Daylio and Replika as they were on two ends of the spectrum. Daylio is a very simple journaling app that allows the user to track their moods and activities. There was

a gamified feature where if you could maintain a streak, you could unlock achievements. Replika on the other hand, is an AI chatbot. The AI’s personality changes over time to match the user’s. There are also activity blocks that tackle various healthy mental habits the user can engage with that change on a daily basis.

I wanted to see which features had the most impact on engagement after a week of interaction with no intervention or reminders on my part.

Even though Replika was more varied and engaging, it was difficult to remember to interact with it on a daily basis as time commitment was too high. Daylio was simple and easy to interact with, however it was too stagnant and users got bored of it easily. The aim is to achieve a balance of the following in order of importance for achieving engaging rituals:

Low time commitment

Varied activities

Gamified interaction

Tracking and trend visualization

Available 24/7

It is important to note that for Replika, low engagement was partly because current technology for developing responsive and contextually sensitive AI chatbots for dealing with emotional experiences is yet to reach expectations. This is important to keep in mind.

Another important interaction that validated how AI could be beneficial in the mental health space is when I had a follow up interview with an individual who said the following in his end- of-experiment survey:

“Well, one of my love languages is words of affirmation. Although I’m not looking to have a ‘relationship’ relationship with the bot, it is nice to receive comments that would be more difficult to say especially with stigmas and filters when it comes to social interaction”

In the follow up interview, he expanded by saying that as

a heterosexual male, it was rare to receive such outright compliments (as shown in the screenshots above). It’s also difficult for him to say these things to other people in certain societies (in canada, it’d be perfectly normal, but in the states where he’s working now, it would be weird), for fear it of being misconstrued. It was a refreshing interaction for him.

Physical Embodiment

While I was unable to follow up and test how a physical presence would affect engagement with the system due to Covid-19, I still wanted to survey acceptable physical features, under the assumption that visual and auditory monitoring would be used due to it’s initial high acceptance rate.

Research

Before I began conducting my interviews, I read several papers regarding physical appearance of companion robots, as well as research into the uncanny valley and human expectations toward robots.

Echoing a previous insight with Replika, appearance and behavior should be consistent with each other. Even the slightest inconsistencies can create an unsettling effect. This is consistent with AI ethical guidelines of transparency and trust.

An interesting insight I had not considered before indicated that an individual’s extroversion is negatively correlated to how proactive they want the robot to be.

Interviews

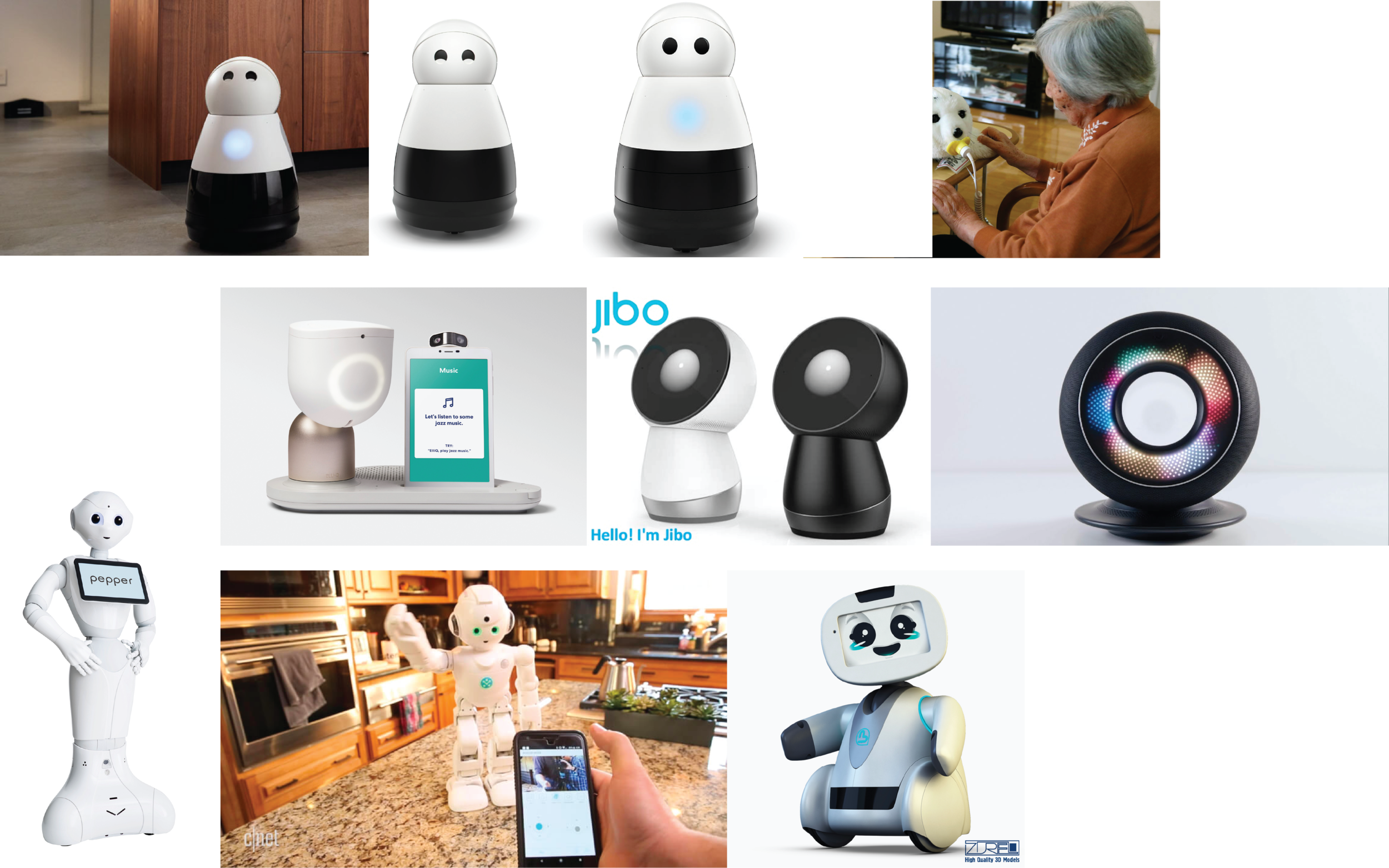

I chose to use a range of existing robots that had their own unique characteristics in order to understand which ones were valued and which ones were offputting for young adults in the context of monitoring for mental health.

In terms of appearance, the interviews reaffirmed that the physical embodiment of the system needed to retain the authenticity of being a machine. They did not like duality of any sort. For example, when the “face” could change from a face to a storybook. People were distrustful if the robot tried too hard be friendly and preferred when the robot remained a neutral tool.

They really disliked when the robot seemed to appear humanoid. The size seemed to offset the humanoid feature. The larger the robot, the more threatening the humanoid shape seemed. For example, Pepper seemed more intimidating than Kuri, even though both were humanoid robots that could roam freely around the home.

In the context of health monitoring, they did not like it if the robot had something similar to an “eye”, as it made them even more aware that they were being monitored. For example, even though they are aware that Alexa by Amazon listens in the background 24/7, they are less threatened by it because they are not constantly reminded of the fact.

Regarding mobility, in the context of health monitoring, they did not want the system to be mobile, as they wanted it to be readily available when they needed it. Rather than the convenience of having the system following them, they wanted the autonomy and control of being able to initiate engagement with the system when they wanted to.

Even though humanoid features were off-putting, when it came to health monitoring and conversations, they were fine with the system having a human voice.

In the next phase, I would want to continue researching what kind of interactions would help create an emotionally durable bond, as well as what kind of gamification would encourage the most engagement. I also want to do more physical prototyping and user experiments to see if the form could be improved upon. Currently, it’s just a very basic form that satisfies the insights from the project.

Final Concept: Ripple

Ripple is a one stop shop kit to introduce users to a set of healthy mental habits based off of mindfulness cognitive behavioral therapy and combining what I’ve learned about how to integrate a ritual into daily life for young adults. It has a physical component and an app component. The physical component has a speaker and a camera that guides the user through yoga poses and gives feedback on how to adjust for correct posture. The speaker can also guide the user through short meditation sessions. The app side has a journaling tracker with a gamified system that encourages daily interaction.

There was a bit of form exploration, though not to the extent I wanted it to be. Initially, Ripple was a set of individual pebbles that each had its own “mini-therapy”, however after conducting more user research, I received responses saying that the pebble system was overcomplicated. People said that they wouldn’t necessarily have a place to keep the pebble when they go out. Girls don’t always have pockets. That it would be odd to take out a pebble in public, which would deter them from using the system. They were also worried about possibly losing the pebble. In the morning, they wouldn’t necessarily want to spend time to think about which “mini-therapy” they’d take with them that day.

After researching more on the methods used in mindfulness cognitive behavioral therapy, I identified a few main methods. Journaling, meditation, yoga and cognitive behavioral therapy. Meditation and yoga could be housed in a physical component which could do image recognition and act as a guide for physical activities. Journaling and CBT could be done in an app. The app side could also serve as a hub to track daily progress.

While the guided yoga and meditation side could also be consolidated into an app, checking the phone first thing in the morning essentially ruins the whole day. A study by the IDC found that nearly 80% of smartphone owners reach for their phones first thing in the morning1. It primes us for distractions, floods us with information and stimuli, leaving us stressed and anxious, our time and attention become hijacked by everything on the phone. Mobile phone use is found to be correlated with stress, sleep disturbances and depression among young adults. Ripple offers a healthy, phone-free alternative way to start the day, helping organize the day’s main goals and offering a boost of yoga or meditation to complement it.

Competitive Analysis: Accessibility

The goal of Ripple is to provide accessible bite-sized therapy that normalizes mental health care. It must therefore be engaging and require little time investment.

Competitive Analysis: Implementation stage

Ripple is not meant to replace professional therapy, but to act as a stepping stone to introduce therapy methods early on in order to combat social stigma and help young adults establish a strong foundation of mental health care.

Competitive Analysis: Cost

While Ripple will not be free, it should still be relatively affordable for young adults who may not have high spending capabilities. At the same time, it cannot be too cheap or the quality of the AI technology embedded within the system will be doubted. Comparing it with existing solutions, while it is not free, it should still be much more accessible than therapy sessions, which could cost from up to £1600, or a robot companion like Olly, which costs £550. Including manufacturing costs, Ripple would cost around £200, which is only slightly more expensive than an Alexa Echo 150. Users have said that they would be willing to spend £350-400 to take care of their mental health at this stage in life.

Ripple is not meant to replace therapy. Instead, it acts as a stepping stone to therapy. It aims to familiarize people with therapy methods and equip them with basic healthy mental habits to hopefully avoid severe depression. However, if things become serious, Ripple will always recommend that they seek a professional for further guidance and assistance.

There is a stigma about mental health. Children are not taught about caring for their mental health in general education. This kit will not solve all the problems or overcome all the barriers, but hopefully it will start a conversation about concrete actions we can take to make mental health a topic taken seriously. With recent events, mental health has become a common topic. I hope that this conversation will continue and evolve into actions in education and the workplace.